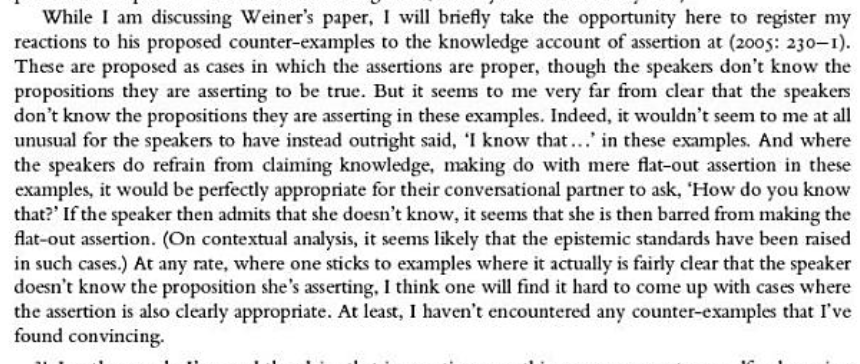

From a long time ago: Here’s part of a footnote from Keith DeRose’s 2009 book The Case for Contextualism Vol. 1 (p. 98, the continuation of footnote 20 from p. 97) about my paper “Must We Know What We Say?” (JSTOR link, open final draft link):

[Text: While I am discussing Weiner’s paper, I will briefly take the opportunity here to register my reactions to his proposed counter-examples to the knowledge account of assertion at (2005: 230-1). These are proposed as cases in which the assertions are proper, though the speakers don’t know the propositions they are asserting to be true. But it seems to me very far from clear that the speakers don’t know the propositions they are asserting in these examples. Indeed, it wouldn’t seem to me at all unusual for the speakers to have instead outright said, ‘I know that…’ in these examples. And where the speakers do refrain from claiming knowledge, making do with mere flat-out assertion in these examples, it would be perfectly appropriate for their conversational partner to ask, ‘How do you know that?’ If the speaker then admits that she doesn’t know, it seems that she is then barred from making the flat-out assertion. (On contextual analysis, it seems likely that the epistemic standards have been raised in such cases.) At any rate, where one sticks to examples where it actually is fairly clear that the speaker doesn’t know the proposition she’s asserting, I think one will find it hard to come up with cases where the assertion is also clearly appropriate. At least, haven’t encountered any counter-examples that I’ve found convincing.]

It’s obviously well past time for me to respond to this, but:

It’s perfectly congenial to what I say in that paper that the speakers know the propositions they assert in my examples. I even say so in the paper. This may be surprising to people who know about the paper, because if it’s known for anything, it’s known for arguing against the knowledge account of assertion and for the truth account. Nevertheless, at the end, in a passage I don’t think anyone ever discusses, I say:

We want our beliefs to be stable, but we also want them to justify assertion. Why should the former outweigh the latter when we ascribe knowledge?

We might think of rescuing the knowledge account by ruling that proper asserters do have knowledge; not by invoking an independent theory of knowledge…, but by identifying the epistemic position required for knowledge with that required for assertability. Then we would have an assertability account of knowledge rather than a knowledge account of assertion.

Which means that I’m willing to allow that the speakers in my examples have knowledge—if we define “knowledge” as “whatever it takes for a speaker to assert properly in a given context.” I give the examples of Jack Aubrey watching the French fleet and saying “The French will attack at nightfall!” or Sherlock Holmes glancing at a crime scene and (uncharacteristically) saying “This is the work of Moriarty!” Both these, I stipulated, are more or less hunches that wouldn’t resist counterevidence.* But I don’t mind if you call them knowledge. You can say that Aubrey knows that the French will attack at nightfall because of his long naval experience, if you like.

*Which is why it’s uncharacteristic of Holmes, who would never make an assertion like that without being able to explain his exact reasoning. In a footnote to his dissertation, Aidan McGlynn correctly rakes me over the coals for getting Moriarty wrong as well. But never mind that.

The thing here is that I meant my paper as an attack on knowledge-first epistemology. One way to knock the concept of knowledge off its pedestal is to argue that it doesn’t play important roles like being the norm of assertion. Another way is to drain the concept of its significance. That is, to say that when we say “Jackie knows that it’s raining,” we’re not getting at a concept that we can build our epistemology on. Which might seem strange, if it’s true that Jackie can properly assert that it’s raining iff she knows it’s raining. How could that not be a fundamental concept? It could not be a fundamental concept if the fact that Jackie knows that it’s raining depends on the fact that she can properly assert that it’s raining, not vice versa.

At the time, my thinking was more friendly to contextualism than it became later. On p. 240 of “Must We Know What We Say?” I even suggest that DeRose’s account (as presented in “Assertion, Knowledge, and Context”) can yield that the Aubrey and Holmes assertions are knowledge while lottery assertions aren’t. But I also argued that the cost is that this means that “knowledge” isn’t robust to counterevidence; they ought to retract their assertions in the face of the slightest counterevidence. That stability is specifically something that Williamson invoked as making knowledge important. He argued that someone who knows that p will be more likely to stick with their actions based on p than someone with a mere justified true belief that p, so knowledge explains actions better than justified true belief does. So my idea was partly: If saving the knowledge account of assertion means giving up the stability of knowledge, it means giving up one of the big motivators of knowledge-first epistemology.

Contextualism seemed even more incompatible with knowledge-first epistemology, though. On its face, if the meaning of “know” varies indexically with context, then there is no such thing as knowledge. The word “me” means whoever the speaker of the constant is, but there’s no Me, only different people who may be speakers. You can’t have a philosophical theory of Me-first anything. If “know” worked like “me,” so that it meant “know by whatever standard of knowledge is in effect in the context,” then the non-linguistic concepts “know” picked out would be a bunch of knowledge-by-standards, not a single concept of knowledge. And I figured that these would vary largely by the strength of justification required, so this would push us to a justification-first conception of epistemology.

(There have definitely been attempts to reconcile contextualism and knowledge-first epistemology, like Jonathan Jenkins Ichikawa’s Contextualizing Knowledge (2017). But that’s what I was thinking at the time.)

So at the time I was fine with contextualism. I would be happy to endorse everything DeRose said in the footnote, including that asking “How do you know?” could raise the standards so that the speaker would have to qualify their assertion. (Though I also thought that, in contexts where the speaker was playing a hunch, “How do you know?” wouldn’t be an appropriate thing to say. When John McLaughlin says “The next man or woman to walk on the moon will be Chinese” there’s no point in saying “How do you know?”)

Later I decided even contextualism didn’t go far enough. Not only is knowledge not a thing in itself, our use of “know” is basically a way to put a gold star on a belief, saying that it does whatever we want belief to do in a given situation. Sometimes we just want the belief to be there, and believing is enough for knowledge. With assertibility, whatever makes something assertable usually makes it knowledge. I’ll talk about that more in another post.